Film, Radio and TV - 6 |

|

"Indies" and

Today, the term "independents" (or "indies") has a different meaning that it did in the 1940s. Today, independent producers and production companies tend to be out-of-the-mainstream operations that resist--some might even say have rebelled against--the perceived content and business-minded limitations of mainstream production companies. Independent producers are important to filmmaking for a number of reasons.

Independent films typically show at special interest theaters, and cable and satellite channels that don't vie for the latest mainstream releases. However, some independent films (once their prove their appeal) are picked up by major studios for distribution. Chariots of Fire,The Blair Witch Project, Leaving Las Vegas, and Sex, Lies and Videotape are just a few examples. (Steven Soderbergh, the director of the latter film, also directed the Universal Studios' hit film Erin Brockovitch, with Julia Roberts. The cinematographer for that film also had an independent film background.)

Helping to boost it to number one box office position were the many fundamentalist churches across the U.S. that promoted it in their pulpits, ran ads for it, and rented theaters and took busloads of people to see it. The comedy, My Big Fat Greek Wedding,

released in 2002, has been the second most successful independent

film. The film first appeared in very limited distribution. My Big Fat Greek Wedding costs about $5-million to make, less than $20-million to market, and within the first few weeks it had made $100-million. Whereas most new releases stay in the top-10 listings for only a week or two, My Big Fat Greek Wedding stayed in the top-10 for months, and in 2003, CBS launched an unsuccessful TV series based on the film. Like some other highly successful films, it was first turned down by the major film distributors on the basis of (they thought) limited profit potential. Fortunately, the film had been produced by Tom Hanks and Rita Wilson, who had the contacts to eventually guide it into the mainstream. A documentary film released (after much controversy) in June, 2004, set a new record for its genre. Michael Moore's Fahrenheit 9/11, an unabashed attack on the the Bush administration, saw people lined up outside of theaters the day that it opened. No documentary had ever generated so much interest (or so much profit). Here is a list of the most popular documentaries in the last ten years and the revenue generated to late-2004.

|

|

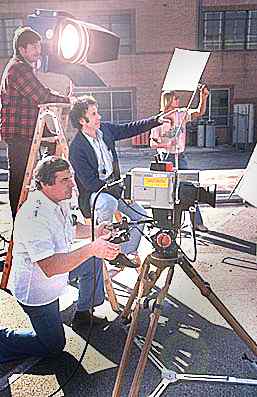

Shooting 40 minutes of film costs about $10,000, while shooting 40-minutes of videotape costs only $70. A video production team working on location is shown on the left. Today, most audiences can't see a difference in quality between good video projectors used in theaters (referred to as electronic cinema, or E-cinema) and traditional 35mm film projection systems. Although the initial cost of E-cinema is much greater than film, the industry could save billions of dollars each year by switching to e-cinema. The key differences between film and video are A number of well-known mainstream film people actively support the independent film cause. One of the best-known is Robert Redford and his Sundance Institute, which is devoted to training new talent.

The content of films gained the legal protection of the First Amendment after the Supreme Court's Burstyn vs. Wilson decision in 1952. It took 50 years, but court finally decided that films were "a significant medium for the communication of ideas." Even though films had First Amendment freedom after 1952, the Hays' Production Code Administration (PCA) seal of approval was still used to determine what was acceptable and not acceptable in film content. (You will recall from a previous module that once Hollywood got on more secure financial footing after the depression, the code once again became important.) Hand-in-hand with the production code was the Catholic Church's Legion of Decency that banned such films as Ingmar Bergman's classic film The Silence and Michelangelo Antonioni's Blow Up. At the same time they endorsed films such as Godzilla vs. the Thing. Imprudent judgments such as these set the stage for rebellion--even when producers were faced with a $25,000 fine for disregarding the code. The well-known director Otto Premminger challenged the code when United Artists agreed to release his film, The Moon Is Blue, in 1953, without the Production Code Administration (PCA) seal of approval. The film had been denied approval because it contained such words as virgin and mistress, which were seen as being unacceptable, even for adult ears. Three years later, Premminger directed Man with the Golden Arm, a film about drug addition. It was also released without the PCA seal of approval. Since both films were highly successful, the power of the PCA code was essentially broken. In 1966, Jack Valenti, former advisor to President Lyndon Johnson, took over as president of the Motion Picture Producers Association and made numerous changes. (After several decades, as president, Valenti retired in June, 2004 and was replaced by Dan Glickman.) Once again, things seemed to be moving a bit too fast for much of the public, and so Valenti instituted a rating system patterned after the one used in Great Britain.

Although Valenti sees this rating system as being advisory only, many feel that the code ends up having economic control over film content. It's easy to see why. Films that are rated R, and especially NC-17, lose a significant percentage of their potential box office audience. Many newspapers refuse to run ads for NC-17 (and especially X-rated) films. Not being able to advertise a film in a local newspaper is obviously a major handicap. American Beauty, which was awarded the best picture Oscar among 1999 films, was rated R, meaning that children can't see it without an adult present. Interestingly, a grade school teacher, who thought that young people should consider the film's message, showed it to her class in early 2000, and as a result, was fired from her job. So why not avoid problems and make all films either G or PG-13? First, there's a bit of a bias against them. Films that are given G, or PG ratings are stereotyped as being bland,"kids stuff." Some people, including much of youth market they are designed to protect, tend to shun them. Second, G and PG ratings greatly reduce the chance of including provocative, edgy, and thought-provoking content--the very things that attract younger and more educated audiences. It's important to note that the present system of rating films is based on the conclusions of a committee selected by MPAA president Jack Valenti. The only actual criterion for committee membership is being a parent (with, we assume, quite a bit of free time). The committee members are kept secret, and individual

members The committee's primary criteria for judging films centers on parental responsibility, as they see it. Studios that get a more restricted rating than they want on a film will generally trim down or eliminate scenes that they think the committee may have objected to, and then resubmit the film. At the same time, the studios are never quite sure what the committee has objected to. Specific changes are neither dictated nor suggested by the committee. That, in their mind, would constitute censorship. There's obviously a lot of tension in this process--especially between the studios, who want the widest audience, and writers and directors, who want to keep the film cutting-edge, realistic, and maybe even disturbingly controversial. Can you have it both ways--a G- or PG-rated film that will also appeal to older and more sophisticated audiences? Yes, to a degree. For example, some films have many double-entendres, or statements and even situations that have two meanings. The James Bond films are an example (action for the kids; pretty women, handsome men, and sexual situations for adults). Many animated films represent even better examples. In Aladdin, Shrek, and Finding Nemo, for example, children can enjoy the action and spectacle, while adults pick up on the adult humor that children don't catch. Films that appeal to different age groups are called crossover films.

There has been criticism from independent film producers that the MPAA ratings board uses a stricter set of guidelines in evaluating their films than they do with films produced by large influential studios. Since the rating system is rather subjective and each film is different, this charge is difficult to prove. However, many independent films have initially been rated "NC-17"--the kiss of death, since they can't be advertised in most newspapers. In some cases independent films have had to be repeatedly reedited--much to the consternation of the directors and writers involved--before the MPAA board brought the rating down to "R." This "dual-standard criticism" isn't helped by the fact that the MPAA board is controlled by the major studios, and appeals are handled by representatives of the major film studios and their distributors. |

The

most successful independent film of all time has been Mel Gibson's

The Passion of the Christ, released in 2004, which

was the number one film for several weeks. Although many cited the

film as the best inspirational-religious film of all time, others

said it set a new standard for sustained cinema violence. At least

two people, including a minister, had heart attacks and died while

watching the brutal scenes in the film.

The

most successful independent film of all time has been Mel Gibson's

The Passion of the Christ, released in 2004, which

was the number one film for several weeks. Although many cited the

film as the best inspirational-religious film of all time, others

said it set a new standard for sustained cinema violence. At least

two people, including a minister, had heart attacks and died while

watching the brutal scenes in the film. Once

it became successful, it was quickly picked up by mainstream film

distributors.

Once

it became successful, it was quickly picked up by mainstream film

distributors. Recent

entries in annual independent film festivals, such as the Sundance

Film Festival, have been shot with digital video, a medium that is

not only far less costly than 35mm or 16mm film, but provides major

postproduction (editing, and special effects)

advantages.

Recent

entries in annual independent film festivals, such as the Sundance

Film Festival, have been shot with digital video, a medium that is

not only far less costly than 35mm or 16mm film, but provides major

postproduction (editing, and special effects)

advantages. are rotated out and replaced at regular intervals. As far as

education, film background, etc., Valenti will only say that the members

are "neither gods nor fools."

are rotated out and replaced at regular intervals. As far as

education, film background, etc., Valenti will only say that the members

are "neither gods nor fools."