Film, Radio and TV - 15

|

Foundations of Radio

The average U.S. citizen listens to radio 22 hours a week. In the United States radios outnumber people by more than two-to-one. For people in most countries of the world "radio" represents the number one source of news and information. Even so, all is not well with this pervasive medium. But let's not get ahead of our story, a story that has its roots in The dots and dashes represent letters of the alphabet.

Samuel Morse of Morse code fame

invented this system in 1836. Morse code is still widely used around

the world as a medium of communication--primarily because for long distance

radio communication the dots and dashes survive interference and radio

static much better than the human voice. Morse code is widely used in international radio communication. Amateur radio licenses require Morse code proficiency, and students have been known to give answers to their friends during tests by tapping out words in code--but you didn't hear that here! We'll reproduce the alphabet as it would look in International Morse code. Who knows, you may find yourself in an emergency situation some day and have to tap out an S-O-S distress signal. As you can see, an SOS would be: dot, dot, dot, (pronounced dit, dit dit) dash, dash, dash (pronounced da-da-da), and then dot, dot, dot. )

There are a few additional elements

and characters in international code, but the ones listed above are

the most used.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Of course, the telegraph was just the first of a string of inventions throughout history that threatened the existing order of things. Invariably, people who wanted to hang on to the old way of doing things vigorously fought these new inventions. As we will soon see, newspapers were threatened by radio, and films were threatened by both radio and television. Not too long after the telegraph was invented, Alexander Graham Bell transmitted the human voice over wires for the first time in 1876. An early version of his invention is shown on the right. Soon, his invention moved from the laboratory to the home--and life hasn't been the same since. The version of the telephone shown below was seen in hundreds of thousands of U.S. homes--even up to the mid-1900s. Among other inconveniences, it contained two rather large dry cell batteries that had to be regularly replaced. Most of these telephones were wired in a "party line" configuration, which means that, especially in rural areas, anyone in your neighborhood could listen to your phone conversations. All the phones on the party line rang at one time, no matter who the call was for. Each home had its own ring pattern. Two short rings followed by two long rings might be for the Smith home, while three short rings and one long one might be for the Jones' family. If you were sitting at home bored, or liked to collect gossip, you could just sit and listen to everyone's telephone conversations. It was pretty hard to keep a good secret in those days.

There were no dials or pushbuttons on telephones; you had to place every call thorough an operator and a switchboard. The operator asked the same question ("number please") a few thousand times a day. A cord was plugged into a jack connecting two lines (Note the photo on the right.), and the operator would push a button to ring the phone. Before leaving the line, the operator would wait until someone picked up--or inform you that there was no answer. Given the ability of any number of people to listen in on interesting conversations, the medium actually ended up being a limited form of broadcasting in some communities. This fact not withstanding, the telegraph and telephone were still considered point-to-point communication devices; that is, the messages that were sent were not intended for mass audiences (as in mass communication). In fact, initially, radio wasn't even intended for a mass audience. In the beginning, the Navy tried to reserve the invention solely for its own use--for ship-to-shore and ship-to-ship type communications. But we're getting ahead of our story again. The telegraph and the telephone laid the foundation for radio. Who is responsible for the invention depends on who (and in what country) you ask. In recognition of his achievement, the term "Hertz" is now used as a term for cycles per second, a common unit for the frequency of both sound and radio waves. With the foundation in place, we were just waiting for someone to come along and put these electromagnetic waves to use for sending and receiving signals. Further clouding Marconi's claim to fame is the electrical genius Nikola Tesla, who, according research done for a 1943 Supreme Court decision over patent rights, also transmitted electrical energy though the electromagnetic spectrum before Marconi. Even so, Marconi was much more PR-oriented, and he was able to get himself associated with the invention of radio. (It never hurts to have a good PR agent!) Other countries have some impressive evidence that some of their citizens transmitted radio signals before Marconi. Even so, if you asked the question on some quiz show, you'll be safest with the name "Guglielmo Marconi." Once he proved that wireless transmissions (radio to you and me) could work, Marconi patented the invention in England, and set up the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. His next step was to sell the idea to the marine industry. Soon, the majority of oceangoing ships were all equipped with Marconi's equipment--which, incidentally, made him very rich. Although the concept worked, Marconi's system of generating radio waves was based on rather inelegant electrical "brute force," which, in itself, created some problems. What was needed was a way of electrically amplifying signals--including the human voice.

In 1906, Lee De Forest, created (or "borrowed" the idea for) the audion tube, a vacuum tube that amplified signals. It is widely believed that a Canadian inventor, Reginald Fessenden, actually came up with the idea, but Fessenden didn't seem to make it into the history books for that invention. Maybe another case of weak PR. But, being a bright young man, Fessenden went on to get his name in the history books in another way--by transmitting the first radio program from Massachusetts in 1906. Ship radio operators, who had never heard anything but boring Morse code beeps through their radios, had a Twilight Zone experience at sea they heard Christmas carols on their radios! Fessenden had succeeded in sending music and even the human voice via radio. Not to be outdone, De Forest then staged some broadcasts of his own. Several were from the Eiffel Tower in Paris (a nice setting to generate some good PR). He then went on to broadcast a performance by the famous tenor, Enrico Caruso, from the New York Metropolitan Opera House. Not only did he put himself "on the map" with these broadcasts, but De Forest proved that radio could be an entertainment medium with the potential for mass appeal. Meanwhile, out at sea, something happened that shook the nation. The "unsinkable" luxury liner, the Titanic, the world's largest ship, set out on its maiden voyage in April, 1912. It hit an iceberg--and sank. As everyone knows who has seen the movie, Titanic, about 2,200 people were on board, and most of them perished that night in the icy waters of North Atlantic. But, it could have been even worse. Thanks to the new invention of radio, about 800 were saved. A young radio operator, safely on land, was in charge of monitoring oceanic radio transmissions that night. David Sarnoff, who was later to play a major role in the development of radio and TV in the United States, had just started his new job. Sarnoff received the SOS signal from the Titanic and immediately relayed the information to the nearest ships. As a result, about one-third of the passengers were rescued. It was then that radio became a "household word." In

the early days of radio there was no way to record sound. Everything

had Although the first sound recording device can be traced back to Leon Scott de Martinville, in 1855, it was some time before the concept came out of the laboratory and was developed to the point of being a practical way to record and playback sound. In 1877, Thomas Edison designed the "tinfoil phonograph," which is credited with being the first practical device to record and playback sound. Edison's phonograph (on the right) consisted of a cylindrical drum wrapped in tinfoil and mounted on a threaded axle. He recited "Mary Had a Little Lamb" into the mouthpiece (horn) for the first demonstration. The horn served as both a microphone and a speaker. Today,

it's difficult to appreciate the impact that the phonograph had. Despite

the questionable quality, for the first time people could hear their

own voice and could even hear music that wasn't being played live.

In 1877, an amazed editor of the "The Scientific American,"

wrote: It has been said that Science is never sensational; that it is intellectual, not emotional; but certainly nothing that can be conceived would be more likely to create the profoundest of sensations, to arouse the liveliest of human emotions, than once more to hear the familiar voices of the dead. Yet Science now announces that this is possible, and can be done.... Speech has become, as it were, immortal. Since there were no vacuum tube or transistor amplifiers, the direct audio waves (note photo above) had to be relied upon to imprint the sound on the recording media. The first recordings were made on strips of tinfoil and on wax cylinders, both of which had a very limited life. On December 1, 1898, Danish electrical engineer and inventor Valdemar Poulsen patented the telegraphone, the first practical magnetic sound recorder. Poulsen's recorder used magnetized steel piano wire as the recording medium. Soon, wire recorders begin to appear on the American market. They were sold as It was not until World War II that the magnetic tape common to today's tape recorders was developed in Germany.

Was KDKA the First Although 8XK (now KDKA) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania is widely credited with being the first radio station in the United States, research by Donna Halper and others shows otherwise. Among those who actually took to the airwaves with (somewhat) regular programming before 8XK were SJN, 6XF, 6XE, 2XG, 1XE, 2XN, 2ZK, and 8MK in the United States, XWA in Canada, and even a station in Argentina. Once again, we appear to be looking at a case of superior PR. KDKA, which was owned by Westinghouse, seems to have used their corporate resources to convince journalists and historians that they were the first radio station on the air, despite the fact that newspaper articles of that era mention at least eight other stations that featured regular programming. This being said, it might be safe to say (in case you are asked on a test) that KDKA represents the first radio station to be officially licensed as a commercial radio station by the Department of Commerce in the United States. Despite

the conflicting data, history books commonly list Frank

Conrad,

a Westinghouse engineer, with starting the first radio station to feature

regular programming. The station's call sign was 8XK,

and, as we've noted, it was the same station that was later licensed

as KDKA. Conrad initially played music on 8XK by holding a microphone up to a phonograph. In a short while people were regularly trying to tune in, and Conrad became a mini-celebrity. Westinghouse, who employed Conrad, took notice and decided they could sell a lot more radios (like the one shown here at $10 each) if they expanded Conrad's operations into KDKA. KDKA is now a maximum-power AM radio station still operating in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. We'll let the historians argue the "who was first issue," and just say that by 1920, radio was officially on the scene in the United States. But, it was not going to be smooth sailing for this new medium, as we'll see in the next module. |

To next module

To index © 1996 - 2005, All Rights Reserved.

|

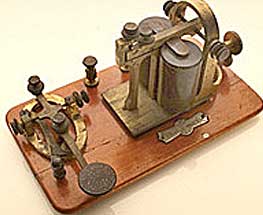

the little device shown here--the telegraph. On the left of the photo is the telegraph key for tapping out messages. On the right are the magnetic coils that respond to incoming signals by making clicking sounds that are spaced to represent dots and dashes. This device represents first electronic form of communication.

the little device shown here--the telegraph. On the left of the photo is the telegraph key for tapping out messages. On the right are the magnetic coils that respond to incoming signals by making clicking sounds that are spaced to represent dots and dashes. This device represents first electronic form of communication.  Bell invented an even better way of communicating: the telephone.

Bell invented an even better way of communicating: the telephone.

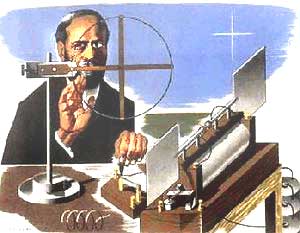

Heinrich Hertz, in 1887, demonstrated that electromagnetic waves could be transmitted through the air. His device for doing this is shown on the left.

Heinrich Hertz, in 1887, demonstrated that electromagnetic waves could be transmitted through the air. His device for doing this is shown on the left.  An Irish-Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi (on the right) is commonly credited for doing that in 1895. But, whether he was actually the first to send signals through the air is open to debate. Some eleven years earlier a dentist named Mahlon Loomis had actually gotten a patent for wireless telegraphy (Morse code by radio).

An Irish-Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi (on the right) is commonly credited for doing that in 1895. But, whether he was actually the first to send signals through the air is open to debate. Some eleven years earlier a dentist named Mahlon Loomis had actually gotten a patent for wireless telegraphy (Morse code by radio).

to

be done live.

to

be done live.

dictation machines and general-purpose sound recorders. One of the best selling brands was the Webcor wire recorder shown on the left.

dictation machines and general-purpose sound recorders. One of the best selling brands was the Webcor wire recorder shown on the left.